Why your hardware product needs a market (or the dangers of being too tech driven)

A couple of days ago I was browsing Twitter when I came across something that caught my eye.

Now, at first I thought this soundbyte (originally from Marc Andreesen, on product/market fit) a bit obvious. After all, this is how businesses work. You provide a product or service, somebody in need pays for that product or service, everybody wins. Do we really need to spell out that, if you're going to start a company, somebody should be willing to pay for your thing? But as I thought about this more, I realized - maybe it's not so obvious. After all, there have been a lot of really smart teams over the years that have managed to overlook that critical question - who is your market? I'll toss out a few examples...

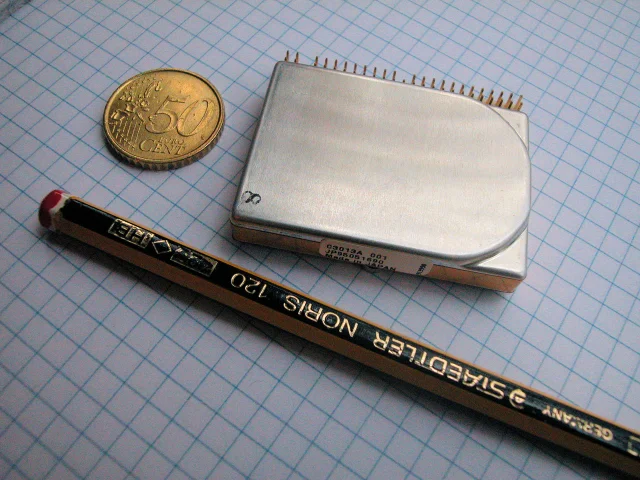

HP's ill-fated Kittyhawk project is now a classic tale of business woe, but one we can still learn from. In 1991, a few senior managers at HP decided to create a team with a special mission. That mission was to develop what would be, at 1.3", the world's smallest disc drive. Recruits for the team even had to sign a creed saying "I am going to build a small, dumb, cheap disk drive." This creed served to reinforce that this team would be different than the other disk drive teams at HP, teams that were focused on maximizing hard drive capacity and minimizing per-megabyte cost. At this point Kittyhawk's marketing team was, in parallel, considering the product's market. They had managers from Nintendo and other companies expressing great interest in the product - if the team could maintain their targeted $50 price point. Product, meet market. But somewhere after this, it all went wrong. The team wanted to hit more aggressive financial goals, so they added features (and cost) to the drive, and went for lucrative nascent markets like the PDAs and ultra-thin laptops. The problem is that these markets either never really materialized (PDAs), or were focused on the capacity/cost metrics typical of disk drives at the time. The Kittyhawk team was left with a product too expensive for the markets that had wanted it, and too underfeatured for the markets they had wanted to sell to. Eventually the product was discontinued - a very expensive and very public waste of time for HP.

A more recent tale is that of Boston's Rethink Robotics. Rethink Robotics was founded in 2008, with the goal of making a robot that could work alongside, and even learn from, real people. The robot would be safe and available at a price-point accessible for small businesses. The team at Rethink seems to have had a very "build it, and they will come" attitude, never diving in deep to figure out what markets were most interested in what they were working on, and how that should inform their engineering. Their first robot, Baxter, had a lukewarm reception across the board. One article on Rethink describes the team interacting with the owner of a small plastic parts producer near Boston. The Rethink team was shocked to discover that the robot's capabilities would need to be doubled before it would be useful at the factory. The company eventually had to lay off almost a quarter of its staff, raise more money, and try to refocus their product on particular market segments. Now with seven years gone by and over 110 million dollars in funding raised, the future of Rethink Robotics is still very much an open question.

Rethink Robotics's first robot, Baxter.

How do companies get to this position, with the money spent, the tech built, and nobody interested in buying? I imagine a good portion of the problem stems from being too tech-driven. Tech-driven teams build cool things because they have the smarts and the passion to do so, because they love to create, and because they want to see their dreams become reality. And - don't get me wrong - I think being tech-driven is fantastic. Tech-driven teams are the innovators, the envelope-pushers, the ones reaching for the future because it's just so close. But when you're focused purely on the technology, it's easy to overlook the question of who is your market. And the question of market is critical to ask - and answer - as soon as possible. Why? Because your market selection feeds back into your product engineering. Think about it. During any product development effort, you have to make engineering tradeoffs. Should the hard drive be less expensive, or more feature complete? Should the robot have two arms that can raise 100 pounds each, or one arm that can raise 200 pounds? Should you prioritize X, or prioritize Y? It's your understanding of your target market that will help you make these engineering choices, and leave you with a product that is both technically exciting, and valuable for your business.