Why Apple doesn’t do user studies

At this point, I’ve written quite a bit about the elements that I see going into making a great hardware product. There is detailed engineering, a solid strategy, and (probably most importantly), a rock solid understanding of your user. I’ve begun to feel like I have a good foundational understanding of developing not only a hardware product, but a hardware business.

That’s why I was so flummoxed recently, when a friend posed an interesting question.

Why doesn’t Apple do user studies?

It’s a fair question. After all, Steve Jobs is famous for saying that the customer doesn’t know what they want. You might have even seen this image (or a similar one) floating around the Internet.

Classic Quora stuff.

This isn’t to say that Apple doesn’t talk to a single person during their product development process (it’s rather unclear what they do). But following a user-centric, iterative prototyping development process (a lá Design Thinking) does not seem to be in their DNA. Why not?

To understand this, we have to take a step back and consider a classic piece of writing — “Why Good Companies Fail to Thrive in Fast-Moving Industries”, an excerpt from The Innovator’s Dilemma, by Clayton Christensen. Here Christensen discusses why companies succeed, and then fail. In a nutshell, it’s because companies become very good at following the standard toolkit of business activities. That’s 3 items:

- Listening to what your customers want

- Investing in new, high-performance products that do what your customers want

- Aggressively pursuing substantial market opportunities

The problem is that these activities lead to a kind of tunnel vision which makes it very hard to perceive and appropriately respond to disruptive technologies. A disruptive technology is one that redefines how a problem is solved. It’s the personal computer vs. the mainframe, cloud-based software vs. big-box retail software, smartphones vs. most everything. These are the innovations that, in hindsight, seem so obviously great. But it’s never that way when they are new. Customers aren’t interested, because your customers aren’t thinking about how their problems might be solved in new and interesting ways. As a result, the market seems small. And disruptive innovations often underperform the existing solution — at least as first.

But — these disruptive solutions come with great new benefits. They might be much easier to use or much cheaper than existing solutions. In time, they gain momentum. They often start by creating new markets for groups for whom their new benefits are ultra-compelling. In time, they encroach upon the traditional markets as well. Ignoring disruptive technologies can and does lead to the death of industry-leading companies.

Christensen’s book is all about knowing when to ignore the standard toolkit, and invest in a disruptive innovation. He asserts confidently:

There are times at which it is right not to listen to customers, right to invest in developing lower-performance products that promise lower margins, and right to aggressively pursue small, rather than substantial, markets.

This, in a nutshell, is why Apple doesn’t do user studies. Simply put —

Apple is in the business of capitalizing on disruptive innovations.

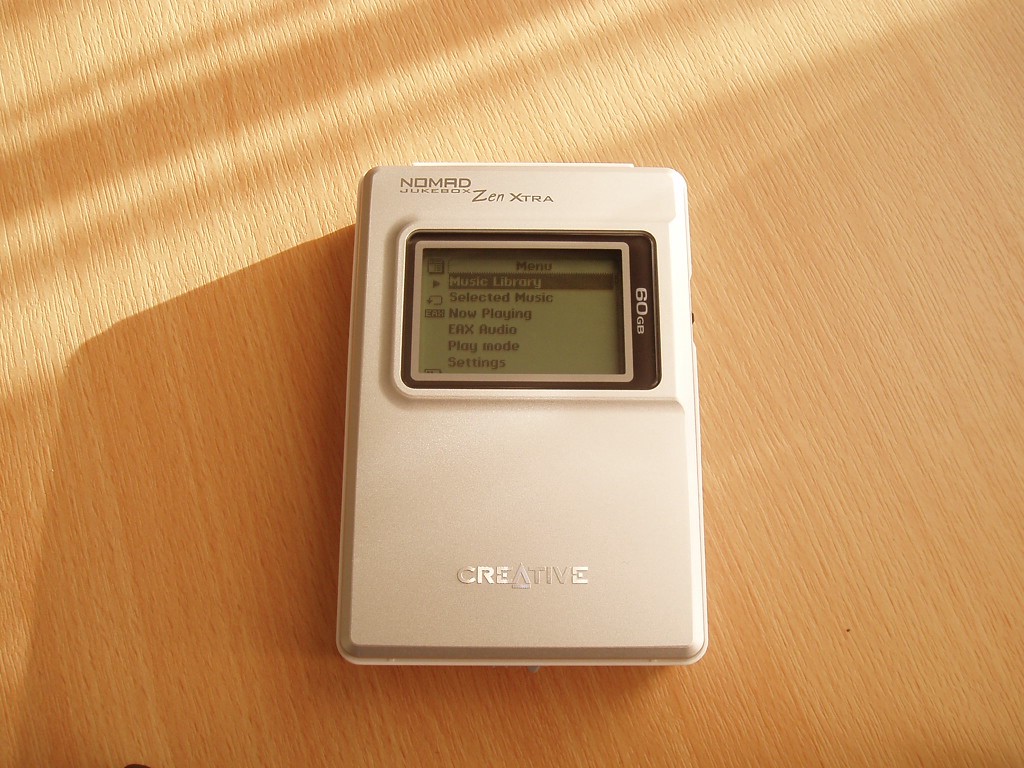

Think about it. Apple rarely does anything truly new. There were MP3 players before the iPod, tablets before the iPad, smartwatches before the Apple Watch, etc. Even with the iPhone, one could make the argument that they had a lot of precedent to work with (T-Mobile’s Sidekick had apps and even an app-store during it’s 2002–2010 run).

The Creative Nomad came out in ’99, well before the iPod.

But Apple identifies these nascent markets, and then gives them the Apple-treatment — great engineering and world-class design. They jump-start disruptive technologies, taking them mainstream and reaping the rewards that properly executing on a disruption can bring.

And because Apple is in the business of disruption, they throw out the standard toolkit — including talking to customers. They believe (like Christensen) that talking to customers can push you in the direction of incremental improvements to a problem’s standard solution — instead of broadly considering exciting new possibilities.

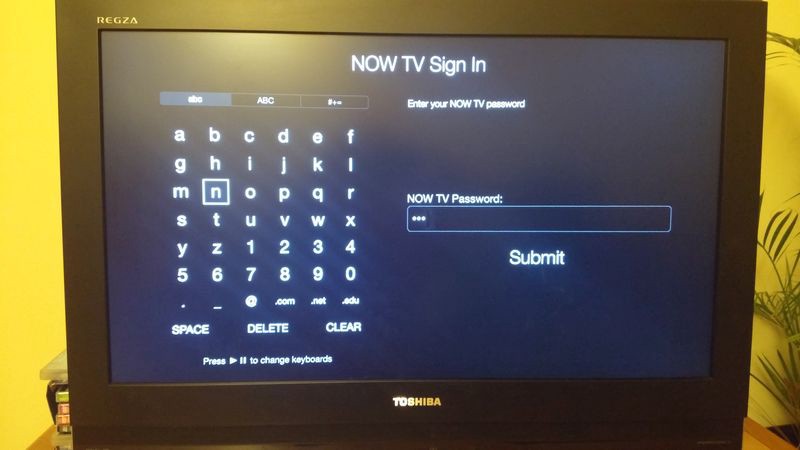

Obviously, this has worked out well for Apple. They are the king of hardware. Indeed, as the world’s most valuable company, they are pretty much the king of everything. But there is danger here as well. In not talking to customers, you can start to miss things. Have you ever tried typing in a password on an Apple TV? It’s an absolutely mind-numbing experience.

This screen is the bane of my existence (from here). Update: new Apple TV is somewhat better.

The truth is, there’s a thin line to be walked here. Talking to people directly about what they want probably won’t be productive, and might even be counter-productive. After all, it’s not your customer’s responsibility to think broadly and creatively about how to solve a problem (it’s yours!). But you still have to deeply understand the problems your user has. If not, you might end up with a product in search of a markets. In hardware, that’s an extremely costly and damaging mistake. But hey, if you can walk this thin line, you might find yourself leading the next Apple someday.